A concurrent session at the CAS Annual Meeting in November 2016 explored the impact of the costs of prescription drugs on workers compensation (WC) medical costs, including:

- the estimated accident year 2014 prescription drug share of WC medical costs,

- the impact of price and utilization changes on prescription drug costs,

- the potential drug cost savings from a drug formulary,

- the increase in physicians dispensing prescription drugs to WC claimants, and

- the use of brand name and generic drugs.

According to recent findings, prescription drug prices increased 11 percent in 2014, which was substantially higher than the 10-year average increase of four percent, said panelist David Colon, ACAS, an associate actuary with the National Council on Compensation Insurance (NCCI). Colon pointed out, however, that prescription drug utilization for that same year declined by four percent, which kept the growth in prescription drug costs per active WC claim to six percent.

According to recent findings, prescription drug prices increased 11 percent in 2014, which was substantially higher than the 10-year average increase of four percent, said panelist David Colon, ACAS, an associate actuary with the National Council on Compensation Insurance (NCCI). Colon pointed out, however, that prescription drug utilization for that same year declined by four percent, which kept the growth in prescription drug costs per active WC claim to six percent.

In addition, he explained that “both physician-dispensed prescription drug prices and utilization increased four percent in 2014 and the share of generic prescription costs went up because of increases in prices and utilization.”

Looking at the big picture, as outlined by Colon, the incremental prescription drug share of total medical costs increases rapidly as WC claims age, with their projected share of total medical costs for accident year 2014 at 17 percent, as projected by NCCI. “It kind of makes sense,” Colon said, “because early on there are a lot of surgeries, a lot of expensive medical bills, and as the claim reaches maximum medical improvement, about half of the costs are going toward prescription drugs.”

Colon explained that costs in the scope of his presentation are the average costs of prescriptions per medical claim with costs being the total dollars paid per claim equaling the price, or what is paid for an individual service, times utilization ‒ the intensity of services provided per claim, that is the number of tablets or capsules of drugs provided per claim and the mix of drugs provided on a claim (for example, OxyContin versus Ibuprofen). Utilization has two more components: whether claimants are getting more prescriptions or less, and if there is a shift to more expensive prescriptions.

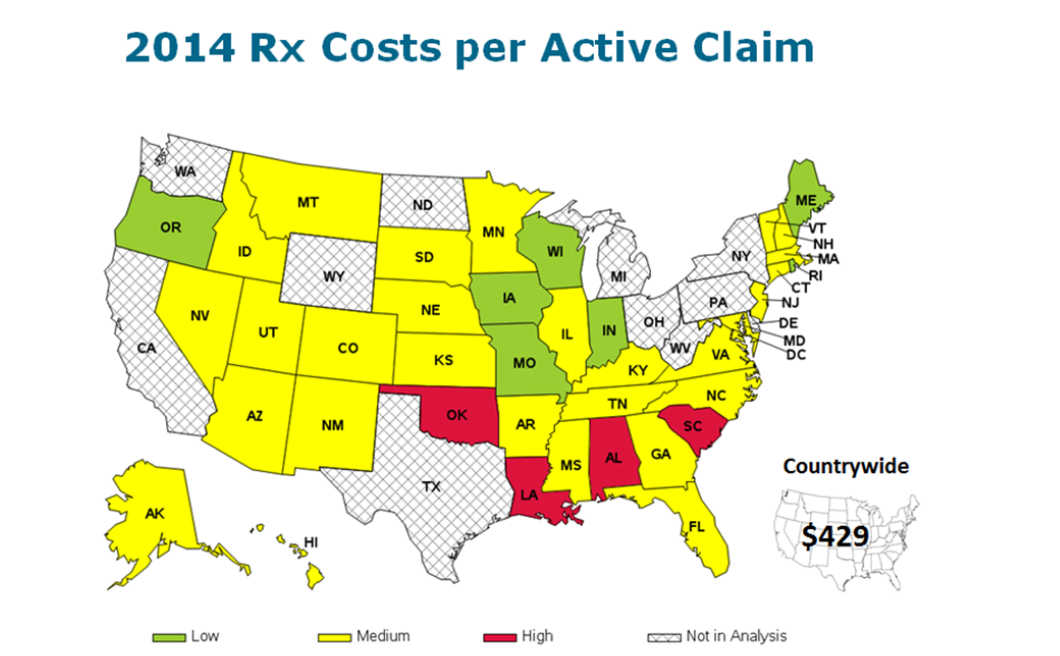

NCCI data for 2014 showed that the average prescription drug costs per active claim was $429 throughout the United States, but in Alabama, Louisiana, Oklahoma and South Carolina, those costs were higher than that average.

“Physician dispensing has been a hot topic in workers’ compensation because it has been on the rise in recent years, adding a lot of costs to the industry,” Colon stated. It could potentially be beneficial for the claimant, he said, with doctors providing the prescription in cases where pharmacies are not easily accessible by the patient. However, “It is a cost driver; the industry knows it and state regulators know it, so there has been a push to control it,” he added.

Summarizing his presentation, Colon said prescription drugs continue to be a significant share of WC costs, while legislative reform and stakeholders’ concerted efforts to contain costs have contributed to dampening the utilization of prescription drugs in workers’ compensation. The NCCI is continuing to look at whether formularies, physician-dispensing laws, and other reform efforts will have their intended impact on the overall workers’ comp experience.

Other organizations are doing research in this area, according to panelist Philip S. Borba, PhD., principal and consulting economist at Milliman. Borba listed the Workers Compensation Research Institute (WCRI), the California Workers Compensation Institute and the Rand Corporation among them.

“A drug formulary seems to be where a lot of states are going, particularly California, because it is such a large part of the workers’ comp business and by legislative mandate it has to have a drug formulary in place by July 1, 2017,” said Borba. It is moving from guidelines – the types of drugs that can be used to treat a specific condition, as many states have done in the past — to formularies, where there are approved drugs that can be prescribed for use.

Borba said a recent research report by the Rand Corporation is useful in laying out what would be needed to put together a drug formulary in California. The report lists a six-point criteria and compares how that criteria matches up to five formularies currently in place:

- formularies for the state workers compensation funds in Washington and Ohio,

- formularies for two sets of workers compensation treatment guidelines in place in California, and

- the formulary for MediCal, California’s Medicare program.

Borba pointed out that a WCRI study found that physician-dispensed drug costs were about twice as high as those dispensed through a pharmacy. And he said in states that have approved reforms to physician dispensing, the percentage of prescriptions that were physician-dispensed went down, starting with Illinois, which had the highest rate before reform, to Florida, which recorded a significant decrease after their reforms were put into place.

“A disturbing finding in the WCRI report, however, is that while the percent of drugs that were physician-dispensed went down, the prices paid to physicians for one of the highest dispensed drugs increased after the reform,” he said, adding that the reforms to physician-dispensed drugs didn’t always lead to a decrease in prices. Also, prices for generic drugs dispensed by physicians have increased more than for generics dispensed by pharmacies, Borba noted.